SEJournal Online is the digital news magazine of the Society of Environmental Journalists. Learn more about SEJournal Online, including submission, subscription and advertising information.

|

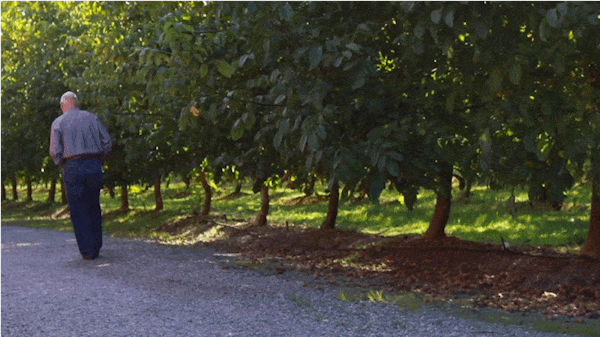

| Farmer Randy Fiorini walks through his Merced County walnut orchard, above. Fiorini Ranch has nearly tripled its production of cling peaches since the 1970s by transitioning to drip irrigation lines seen above. Photo: Madison Pobis/…& the West. Click to enlarge. |

EJ Academy: Searching for Narrative in the Groundwater Where It Happens

By Madison Pobis

I am a field scientist by training, a filmmaker by practice and an ocean nerd by choice. I am perfectly at home letting my fingers go numb while diving in a kelp forest or spending hours with a subject documenting their quirky anecdotes on camera.

In the fall of 2019, I joined the distinctly named …& the West blog run by The Bill Lane Center for the American West at Stanford University in order to complete the practicum requirement for my master’s program in Earth systems and environmental communication.

The center, named after the long-time publisher of Sunset magazine, works with Stanford University students, faculty and outside partners to address a range of challenges facing the Western United States.

The blog’s focus on the environmental future of California and Western North America, as well as on multimedia, offered a new opportunity to hone my writing skills and report with both feet firmly planted on dry land.

But, like a fish out of water, I struggled to find a story idea.

I scoured Google Scholar for academic papers with keywords like “conservation,” “species” and “habitat” in the hopes of hitting on some random ecological success. But beyond that, I was looking for narrative elements — characters, scenes, dialogue and details that would pull a reader into the American West.

Then I found a theoretical paper that proposed an intuitive solution to a looming behemoth of a problem.

Several thousand square kilometers of land in the San Joaquin Desert will become available in the next several decades as depleted groundwater makes the parcels untenable for farming.

Could some of that land be used to restore habitat for endangered species?

Quagmire of acronyms, polarization and white papers

I pitched the idea, outlining a feel-good story about turning bad luck with water into something good for the environment.

My editor, a grizzled veteran in reporting on California groundwater, immediately poked at the gaping holes in my initial pitch.

|

| A farmer holds up a peach from a harvest on Fiorini Ranch in 1951. This archival footage was a crucial find for the author, establishing a visual style to connect the past and present across the three farmer video vignettes. Photo: Courtesy of Randy Fiorini. Click to enlarge. |

Just how much land are we talking about? What happens to the rest of the land that can’t be used for conservation? Will farmers be compensated for this dramatic conversion?

Then she mentioned a term that I couldn’t properly define at the time but would ultimately become the slug for my story: fallow.

I dove headfirst into the world of California groundwater legislation and quickly discovered a quagmire of acronyms, polarized communities and policy white papers.

For too long, farmers in California had relied on surface water when it was available and fell back on groundwater when it wasn’t. The California Sustainable Groundwater Management Act, or SGMA (pronounced like the Greek letter), forces local agencies to make a plan for bringing those groundwater basins into balance by 2040.

The first draft of those plans for critically overdrafted basins would be due by January of 2020 — a deadline that aligned perfectly with the end of my practicum and served as a news peg for a deep dive into groundwater sustainability.

Maximizing the power of multimedia

I specialize in multimedia storytelling, which means thinking critically about the advantages and limitations of different media in order to maximize the impact of a story. Ideally, those media are integrated seamlessly so that a reader is rewarded with a more complex and fulfilling experience when they engage with all the elements on the page.

While interviewing experts and groundwater managers about all my lingering questions related to fallowing farmland in the San Joaquin Valley, I realized that video could act as the connective tissue between the story’s common threads and the individual hurdles facing stakeholders.

Arranging the elements in a compelling way would make all the difference between a piece hovering at a bird’s-eye view and a feature that would get to the heart of what’s at stake for small family farmers.

Although video is less information dense than writing, it delivers an intimacy and personal perspective that can be nearly impossible to achieve within a defined word count.

I knew that our readers would benefit from

the sensory and emotional richness of video

narratives embedded into that written context.

Just as I was looking for an easier way into the dry jargon of groundwater legislation, I knew that our readers would benefit from the sensory and emotional richness of video narratives embedded into that written context.

I set out for almond and walnut country in Turlock, Calif., to film three generational farmers grappling with imminent groundwater cutbacks on their land.

Instead of prodding them on the cumbersome details of forming agencies and going to meetings, I asked them to talk about their favorite memories of the area — what it was like to grow up and make a living in the same orchards their parents had passed on to them. And even more so, what it was like to see it hang in the balance.

The instinct to use video as my entry point for emotional resonance served as a guide while editing the vignettes. Since I had limited time and resources to shoot b-roll, or visual coverage, archival footage from the families and the California Department of Water Resources was a vital resource for creating a consistent tone and visual interest.

The ladder of abstraction

Anchoring the story around the three video vignettes of the farmers provided an additional benefit when composing the structure. They established super-stable first rungs for moving up and down the so-called ladder of abstraction.

The ladder is a mental model developed by S.I. Hayakawa, a politician and English professor, for how to move from concrete examples to broader abstract ideas.

Although the ladder of abstraction is often used to describe language and critical thinking skills, it can also be used as a narrative device for zooming in and out on your story. As a reporter, I have found that it’s a powerful tool for visualizing the perspectives that you are presenting to a reader.

The farmers I featured, Randy Fiorini, Scott Severson and Al Rossini, could simultaneously speak as concrete individuals about their experience, while also representing larger themes in the piece — unintended consequences, a precarious future and conflict with environmental groups, respectively.

By the end of the story, readers have traveled up and down the ladder, and gained both the information and the emotional context they need to understand why the law will impact farmers in the long term.

The spaces where issues impact lives

Throughout the process of writing the story, my editors challenged me to answer specific questions with thorough responses where I could.

One that continued to surface was, “What will farmers do with the land that they don’t have the water to farm?” In some cases, we found that farmers were transitioning to higher-value permanent crops or negotiating with companies to install green energy technology.

For the most part, there aren’t enough good

solutions to go around for the more than half

a million acres that will come out of production

to bring the groundwater basins into balance.

But for the most part, there aren’t enough good solutions to go around for the more than half a million acres that will come out of production to bring the groundwater basins into balance.

Whereas big agricultural corporations have staff entirely dedicated to navigating the new law’s regulations, many family farmers and immigrant farmers will be hit hardest by SGMA because they lack the clout and resources to engage in the process.

Instead, they do what they can to keep the ranches and orchards passed down to them from grandparents running until their local agencies can release more specific guidance.

My hope is that readers will come away from the story feeling like they have traveled with me across place and time through California’s groundwater landscape, emerging on the other side with a greater understanding of who has something to gain or to lose because of SGMA.

At the end of the day of filming in Turlock, I was walking through the orchards with Randy, one of the generational farmers featured in a video chapter.

The sun hung low in the sky, swollen and glowing like one of his grandfather’s peaches. His black lab, Yeti, trotted just ahead.

He told me that most of the people who wrote about groundwater issues made a few phone calls to the Sacramento bureaucratic offices and maybe a scientist or two. Few of them took the time to travel to the spaces where those issues impacted folks’ lives.

You are the verbs that you do. I’m still a field scientist at heart. And now I can say I’m a field journalist too.

Madison Pobis is the science communication Fellow at the Monterey Bay Aquarium Research Institute in Moss Landing, Calif., where she is using multimedia to highlight groundbreaking ocean projects. While a student she worked as an editorial intern for bioGraphic reporting on science and environmental stories. She graduated from Stanford University with a B.S. and M.A. in June 2020. Her piece, “Small Farmers Wait for California's Groundwater Hammer to Fall,” won first place for outstanding student reporting in the 2020 Society of Environmental Journalists’ Annual Awards for Reporting on the Environment.

* From the weekly news magazine SEJournal Online, Vol. 5, No. 45. Content from each new issue of SEJournal Online is available to the public via the SEJournal Online main page. Subscribe to the e-newsletter here. And see past issues of the SEJournal archived here.